Nineteenth Century: food and botanical influences

In 1811, Governor Macquarie began building stone walls to separate the Domain from the town. Under the guidance of Mrs Macquarie, the landscape was shaped and exotic trees planted. Drives and view sites replaced some of the surviving indigenous vegetation.

By 1814, Macquarie’s concept of a “Government Garden” in Farm Cove began with the planting of two Norfolk Island Pines (Araucaria heterophylla). Following completion of Mrs Macquarie’s Road in 1816, exotic English Oaks (Quercus robur) and Stone Pines (Pinus pinea) and indigenous Swamp Mahogany (Eucalyptus robusta) and Blackbutts (Eucalyptus pilularis) were planted along the road. The surviving Swamp Mahoganies, along the stone wall in what is now the Royal Botanic Gardens, are the earliest remnant civic planting in Australia.

Early Sydney gardens were essentially productive and modelled on the simple square patterns of walled kitchen gardens of Britain. Imported fruit and olive trees (Olea europaea) were among the species planted in these food gardens.

From 1816, the Sydney Botanic Gardens played a key role in exchanging plant specimens, with collections of Australian flora sent to British and European botanic gardens. Sydney quickly became a vital part of trade with other gardens around the globe, including Calcutta, Penang, Singapore, Mauritius, St. Vincent, Jamaica, Trinidad and Cape Town.

Initially access to the botanic gardens was restricted to the ‘gentry’, but in 1831 it was opened to the general public. Most plantings in the botanic gardens related to kitchen needs. Nevertheless, a vast range of botanical specimens was introduced to the Colony, providing the early influences and direction which would later come to dominate the city’s landscapes.

Stately Norfolk Island Pines appealed to the British taste for conifers and by the 1820’s graced the front lawns of many colonial houses and public buildings. These pines and the related Hoop Pine (Araucaria cunninghamii), discovered in Moreton Bay in the 1820’s, also served as navigational beacons and markers on the harbour. The towering conifers have been a distinctive part of the Sydney skyline for almost two hundred years.

Among other significant trees planted during this period were Stone Pines (Pinus pinea) and English Oaks (Quercus robur).

Romantic landscapes

The cultural landscapes of the City are closely linked to our natural heritage and the picturesque and idealised landscapes of the early to mid-nineteenth century. As wealth was created, gardens and estates came to signify a new permanence.

Australian gardens attempted to emulate the grand gardens of Europe, borrowing on the traditions of the English landscape school and European romanticism. Francis Greenway, the Civil Architect under Governor Macquarie, outlined a largely unrealised vision for the Domain to be planted in the English landscape style.

From the 1830s onwards, these romantic, idealised landscapes were gradually supplanted by the Gardenesque style, and influenced by formal Georgian, Regency, Classical, Victorian and Italianate architectural styles of the period.

It was also a time of great global exploration and interest in botanical collections. Themes for the planting of public and private gardens were inspired by the stories of early explorers, cedar-cutters and plant collectors.

Among the famous botanists whose discoveries influenced tree plantings in Sydney were William Paterson, Charles Fraser, brothers Allan and Richard Cunningham, John Carne Bidwill and Ludwig Leichhardt and their Aboriginal guides.

Rainforest botanical discoveries

During the 1820s to1840s a vast range of exciting subtropical rainforest species was discovered by colonial botanists. Many new species were made available to the public. The introduction of rainforest plants transformed some of the desiccated scrubs and woodlands of Sydney.

At that stage the landscape around Sydney harbour and to the west was hostile and relentless, offering no respite for early settlers. The poor conditions and general infertility of soils hindered agricultural production. There were few similarities with the bucolic landscapes of England and northern Europe,

In comparison, the rainforests of the Illawara in the south and along the northern rivers of NSW offered unparalleled opportunities for tapping into a rich resource. Stories of extraordinary botanical diversity attracted enormous popular interest. These subtropical landscapes became the inspiration for new idealised landscapes, dominated by lush, broadleaf species.

Moreton Bay Fig (Ficus macrophylla) was a relatively early ornamental introduction to colonial gardens and was used as a major landscape element through the nineteenth century. These magnificent figs, with their spreading evergreen canopies, were ideally suited to grand garden schemes.

An avenue of Moreton Bay Figs was planted in the Domain around 1847. Charles Moore, who was Director of the Sydney Botanic Gardens for almost 50 years from 1848 to1896, and nurserymen Michael Guilfoyle and his son William promoted the use of these figs and other rainforest specimens for park planting throughout the Victorian era.

The collections included native rainforest specimens with outstanding floral displays such as the Silky Oak (Grevillea robusta), Blackbean (Castanospermum australe), Illawarra Flame Tree (Brachychityon acerifolius), Queensland Lacebark (Brachychiton discolor) and Firewheel Tree (Stenocarpus sinuatus).

Other species such as Crow’s Ash (Flindersia australis), Plum Pine (Podocarpus elatus), Tuckeroo (Cupaniopsis anacardioides), Tulipwood (Harpullia pendula), Brush Box (Lophostemon confertus) and Tulip Oak (Argyrodendron actinophyllum) were used more for their attractive dark, glossy evergreen foliage.

The native trees were mixed with a wide range of exotics, many with broadleaf, evergreen character such as the Camphor Laurel (Cinnamomum camphora), Holm Oak (Quercus ilex), Jacaranda (Jacaranda mimosifolia) and American Bull Bay Magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora). Exotic conifers, including Chir Pine (Pinus roxburghii) Loblolly Pine (Pinus taeda) and Monterey Pines (Pinus radiata), were also popular.

So a multitude of ornamental and cultivated species was introduced into Sydney gardens and parklands. Many species failed while others flourished. This process of selection influenced the way gardens developed.

The Landscape and Picturesque styles were merged and overlayed with a new approach that reflected the array of botanical specimens sourced from around the globe. These collections grew increasingly complex and eclectic by nature.

The Gardenesque style,1835–1890, gained momentum after the Great Exhibition held in London in 1851. In particular, the introduction of glasshouses allowed subtropical specimens to be grown in cold climates. The popularity of botanical curiosities influenced the types of exotic collections and character of both private gardens and public open space throughout Sydney.

Great estates and villas

One of the most important collections of significant trees lies within the former grounds of Elizabeth Bay estate. The 21 hectares of land at Elizabeth Bay was granted to famous explorer and entomologist Alexander Macleay, Colonial Secretary of New South Wales, in 1826.

Macleay and landscape gardener Thomas Shepherd were heavily influenced by the English Landscape style. Macleay’s garden and other famous villas, including Captain Piper’s estate ‘Henrietta Villa’, Macarthur’s ‘Camden Park’ and the Macleay’s ‘Brownlow Hill’ all reflected these influences. These villas and estates, with their once extensive gardens, provide a rich, albeit fragmented heritage of significant trees.

Nurseryman Robert Henderson, Shepherd’s son-in-law, supervised the layout of the Elizabeth Bay estate gardens. In an era when most landowners cleared all native vegetation, a report stated that Macleay “never suffered a tree of any kind to be destroyed”. He retained the rich indigenous vegetation on the scarps and rock outcrops while enhancing the landscape in the picturesque style. It was a visionary approach.

The centrepiece of the estate was Elizabeth Bay House, a magnificent Greek Revival-style villa, completed in 1837. Macleay established a library, a famous entomological collection and one of the greatest botanical collections in the Colony. New plant introductions and their sources were methodically recorded in two surviving notebooks (Plants received, c1826-1840 and Seeds received, 1836-1857). His legacy was continued by his son William Sharp Macleay.

The gardens contained exotic fruit trees from around the world. In 1835, Charles Von Hugel noted that “pawpaw, guava and many plants from India were flourishing. The gardens of ‘Boomerang’, located within the former orchard of Elizabeth Bay House, still retain a very old specimen Mango (Mangifera indica) from India and an Avocado (Persea gratissima) from Central America or the West Indies.

The remaining trees of the once vast Elizabeth Bay estate collection are today scattered through private gardens of high-rise apartment blocks. These significant trees have somehow survived an increasingly urbanised and hostile environment.

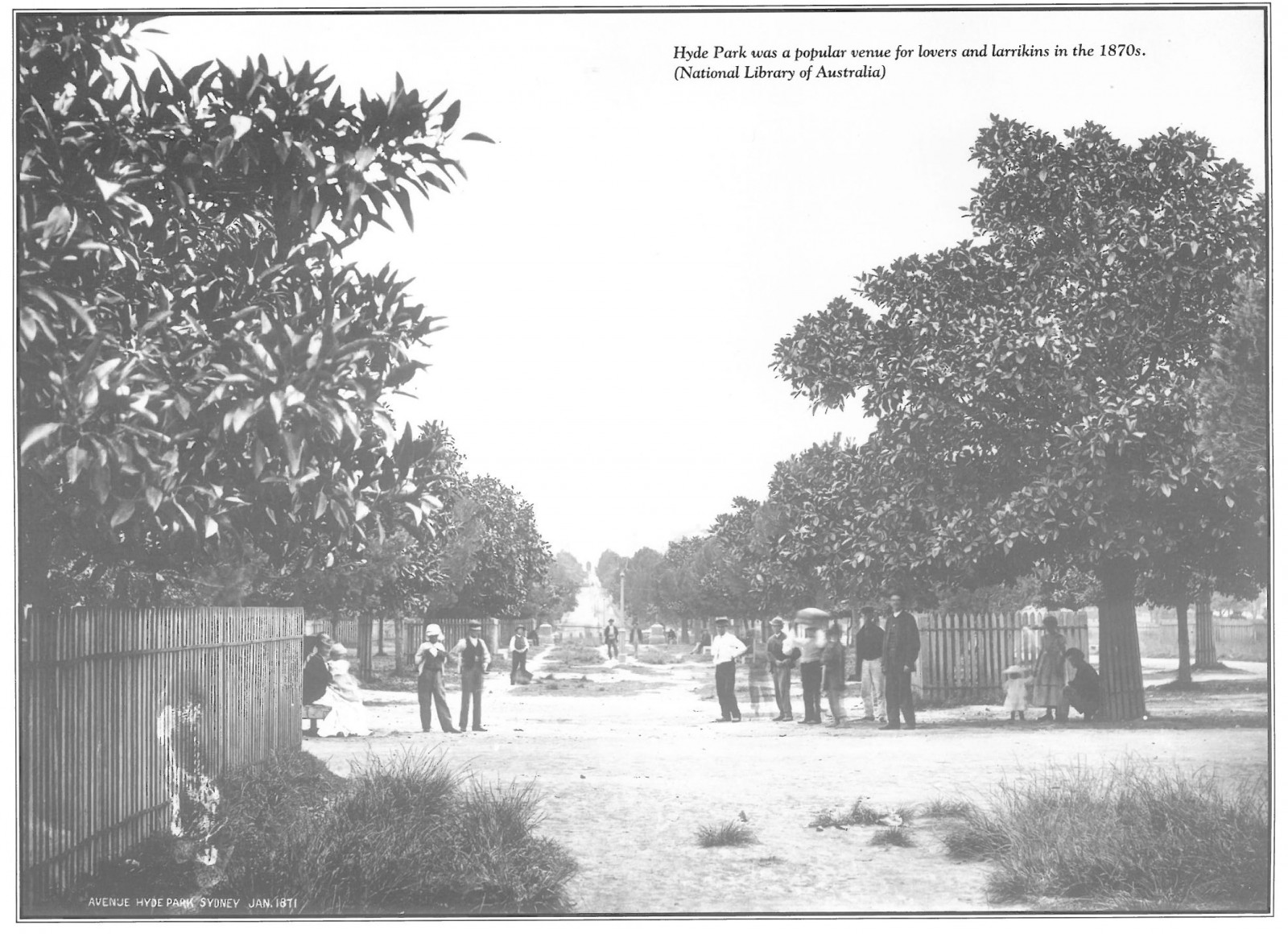

Victorian row plantings

The great Victorian landscapes of row plantings and individual specimen plantings have come to define much of the City’s visual and aesthetic character. These visionary landscapes were influenced by a range of people, notably Charles Moore, Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens (1848-1896).

By the nineteenth century, new trees were planted in areas largely devoid of natural vegetation, due to timber cutting, broad-scale clearing, agricultural development and encroaching urbanisation.

The legacy of Victorian public planting has matured to produce landscapes dominated by massive native figs, particularly Moreton Bay Fig and Port Jackson Fig (Ficus rubiginosa). Used predominantly in row plantings along parkland boundaries, the figs were not planted in formal, rigid lines. Instead they were arranged in a more naturalistic way, overlapping planted elements and other notable specimens.

The spaces between the figs were embellished with native and exotic species, including the Deciduous Fig (Ficus superba var. henneana) and exotics, particularly the hardy Holm Oak (Quercus ilex) and Camphor Laurel.

Dramatic vertical elements and botanic curiosities were introduced by cluster plantings of pines, including Bunya Pine (Araucaria bidwillii), Cook Pine (Araucaria columnaris) and Queensland Kauri Pine (Agathis robusta). These tall emergents are an important part of the City’s modern skyline

But the spreading, evergreen figs remain the quintessential element in the Victorian boundary plantations. This approach, seen throughout The Domain and Moore Park areas, is repeated in other major public parks of the City of Sydney.

The park boundary plantations have created great streetscapes, including those at:

• Anzac Parade alongside Moore Park,

• Bridge Road flanking Wentworth Park,

• City Road and Broadway alongside Victoria Park,

• Elizabeth and College Streets next to Hyde Park,